These last few days have been very eventful in the Tibetan Buddhist world, and three occurrences in particular have interrupted the normal flow of my work and put me in front of the keyboard (to compile information and write things for the several outlets I’m connected to): the passing of Domang Gyatrul Rinpoche, the media flurry regarding His Holiness the Dalai Lama, and then the passing of one of my first and most important teachers, Lama Zopa Rinpoche.

All three have evoked strong emotional reactions from me, but I’ve been able to maintain a certain level of inner equilibrium by doing something I believe is productive: offering clarifications that can, hopefully, inspire people to continue cultivating wisdom and compassion.

As this turbulent week is coming to a close, I am getting ready for my first in-person class in London (also available online): a session on loving kindness offered as a part of a series on the four immeasurables, or four types of benevolence. Since those are at the heart (pun!) of my own practice and have always been deeply embodied by Lama Zopa Rinpoche (who guided me to these methods in the first place), I know that sitting together with others to generate loving kindness will also feel like a deeply meaningful, healing act.

His Holiness the Dalai Lama and the media

I first heard about the issue upon waking up one morning and seeing a message from an Instagram friend (and a fellow ex-monk) from Thailand. He noticed a strange thing suddenly going viral on Thai twitter, but suspended judgement and asked me about the fuller context. Being still groggy, I could only suggest the video might be edited (which it actually was) and said that we will probably have more context very soon. Since then, I have received similar questions from other people I know—a famous drag performer, a career diplomat, a few classmates and so on.

“Context” is the key word here. As someone currently facilitating a course on insight practices—the essence of which is working against our tendency to decontextualise every aspect of reality we perceive—and as a translator (who knows that words only acquire meaning in a context), I am extremely sensitive to rush judgements made out of context, and am extremely aware of their dangerous nature.

Essentially, we should all think: we’ve actually all done and said things that, if they were to be carefully taken out of context with a certain level of maliciousness (or just sensationalism), would end our reputation. If someone were to care enough to start a campaign, we should hope that at least the people most important to us would take a moment and seek to understand the situation fully, after careful investigation. Such investigation would not make us immune to criticism, but it would offer us the space necessary to have our actions understood correctly.

The media coverage of the incident has been deeply colonial, since it excluded the voices of voices of Tibetans—and Tibetologists, who could offer the precious context on the original expression that His Holiness was trying to translate into English.

It has also been driven by sensationalism and therefore excluded the full version of the video (which presents a completely different picture) and the interviews with the boy and his mother.

Needless to say, it also ignored the Dalai Lama’s blameless record of dealing with people over the last decades of his travels, or his position as one of the leading humanists and pacifists of our time.

Finally, the context itself was omitted: the original (full-length) video is not from a hidden camera, it is from a public event attended by Tibetan and Indian officials alike, along with numerous members of the public, and it was uploaded by the Tibetans themselves to the Voice of America website.

Furthermore, the video did not actually become viral when it was first uploaded; it only started circulating widely right at the moment when mainland China—still heavily pissed by the Dalai Lama’s recent recognition of a very important reincarnate lama and famously seeing his as one of their primary enemies—started its military games imitating an attack on Taiwan. The games, covered by this media noise, went largely unnoticed.

There is no need for me to share my own observations, feelings, or history with the Dalai Lama—I’m not someone important. The only thing important is to offer the full context and to elevate the voices of Tibetans, because they are uniquely capable of knowing the full cultural context; so here are some helpful links (if you haven’t already seen them on my Instagram):

Robert Mayer of Oxford on the original expression (see another description of the same expression here)

On a similar expression used in Amdo Region, where the Dalai Lama is from

A statement from the current Sikyong (Tibetan Prime Minister) Penpa Tsering

Interviews with the boy and his mother right after the event

A statement from His Holiness Sakya Trichen, supreme head of the Sakya tradition

You can find most recent updates at the Tibet Today account.

One thing to understand—shared by the Tibetans within their community discussions—is that the immense harm brought by the sloppy media coverage is not going to undo itself. We all, if we have come to some clarity about the issue by studying everything above, can share this task and elevate the voices of the people whose heritage we have been benefitted by so much.

(As a side note, I have also seen some of my secular colleagues adopt a patronising stance and refuse to look into the issue or too see the colonial nature of this incident, all while continuing to capitalise on what the Tibetans have brought them so generously. That’s not something I can agree with)

Gyatrul Rinpoche and Lama Zopa Rinpoche’s passing

Gyatrul Rinpoche, for me, was a lineage lama—as the main Dzogchen guru of Lama Alan Wallace, he was a teacher of my teacher. I never had a chance to meet him in person in North America, but have received incredible benefit from his books (including A Spacious Path to Freedom), and, of course, from the activity of his Dharma successors, including Lama Alan Wallace and Lama Sangye Khandro. He was instrumental on brining many rare Dzogchen teachings into North America, and then, by extension, to the entire world.

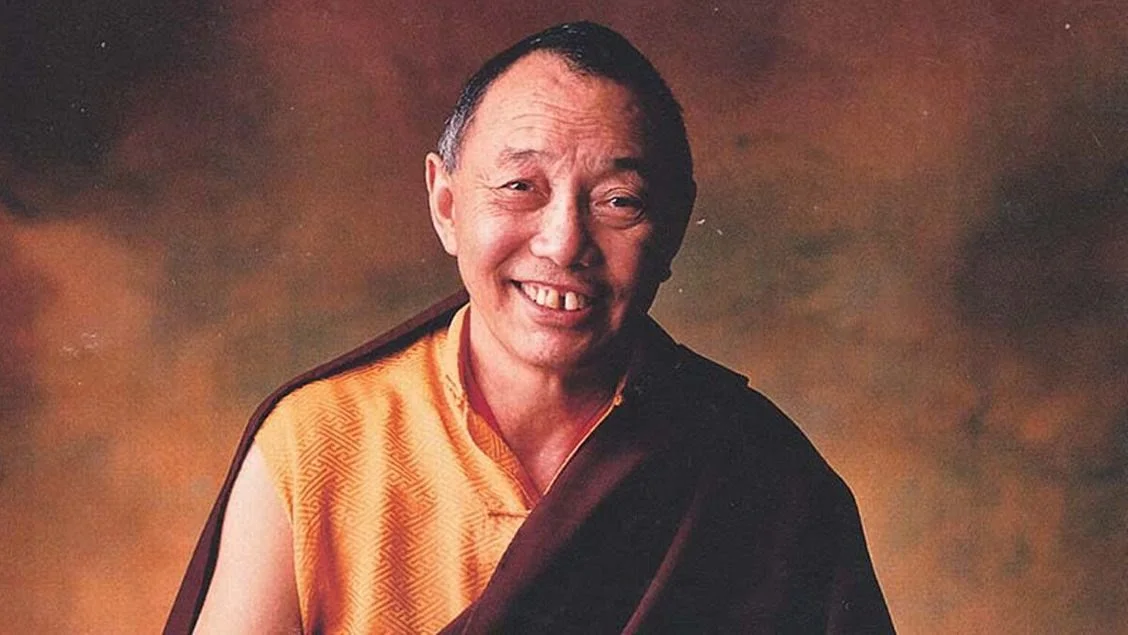

By contrast, Lama Zopa Rinpoche was very much my teacher—one of my root lamas, who especially benefitted me through his teachings on bodhicitta, but also generously dispensed personal advice.

It was Lama Zopa Rinpoche’s guidance that led me to develop an interest (and, through that, a certain understanding) of such practice systems as White Tara and the four immeasurables—things that are now at the heart of my work as an instructor. Lama Zopa Rinpoche was an incredible yogi and a true embodiment of kindness, and him passing away right amidst a smear campaign against his main teacher is a tragic loss for the world. For all of us, it as an invitation to use our wisdom and compassion to greater degree.

The passing of both these teachers leaves their students, in a way, groundless, just like the media campaign covered above. A familiar picture of reality shifts, and we are feeling a bit lost, confused, or forlorn. The great thing is that we have very simple questions that we can ask ourselves — for example, Having carefully analysed the situation, what do I have to offer? And How can I keep my practice alive and vibrant so that it benefits others? As long as we answer these somehow — for example, by turning to the practice of loving kindness — we are on the right track.