My body, like everybody else’s, is constantly undergoing changes. Over the years, I’ve been trained to see it as a field of energy that can be potentially used for good—for example, when attempting to serve others—and yet will keep bringing the inevitable complications which include physical pain and the frustration of age- and sickness-related physical limitations.

The balance of the five elements within our body is extremely fragile, and a small seed (karmic or situational, depending on how you want to see it) can bring us a lot of discomfort. For example, when growing up, I was tormented by incessant intense headaches of unclear origin. These often left me nauseous and would not be affected by any type of medication—I had to complete all my tasks while desperately wishing to find some respite.

These headaches eventually disappeared, but were replaced by horrible face skin problems (one reason for why I don’t have that many photos from my BA years). That, in turn, eventually gave way to chronic, allergy-related pain that occurs at least once a twice a month and occasionally leaves me bent over, waiting for it to pass. That, in turn, might continue on its own or eventually join forces with a number of other maladies and aches, testing my limits on new ways. In the words of arhat Śāriputra, “the aggregates are oppressive”—the unenlightened form or our body, speech, and mind energy is always ready to produce more types of dukkha.

What, then, is the solution? While I do explore all the medicine-related paths towards perfect health and absence of physical discomfort, some things are simply beyond fixing, at least for now. Physical problems are a given—a part of human existence (along with birth, aging, and death). The best I can do, then, is to deal with the unpleasant physical experiences gracefully–with equanimity, compassion, and mindful awareness, sustained at all times in support of self-kindness and kindness towards all beings.

One thing that I’ve learnt in this journey is that health-related (and pain-related) contemplative skills can be learnt as a subject of its own—a “Pain-Management Dharma”, if you may, intimately connected to the Dharma in general and yet providing valuable insights into how to deal with the suffering in the here and now. While playing with the idea of creating more materials related to the practices that have helped me personally, I am honored to present the following list of resources in case they might be of help to you or your loved ones.

Universal source: dealing with sickness and pain

A universal source that covers many aspects of sickness and physical problems (along with the associated types mental anguish) has been compiled by Toni Bernhard, based on her extensive experience of living with chronic illness.

In the two versions of How To Be Sick she explores a wide range of topics and practices that might be of help:

How To Be Sick by Toni Bernhard

How to Be Sick: A Pocket Book by Toni Bernhard

Mindful pain-management

Dealing with any pain that we can’t alleviate through medication or exercise requires a lot of inner resources. In my experience, the main qualities to cultivate for successful pain management are the same we need in our contemplative life in general: focused, clear awareness; love and compassion; wisdom that discerns the true interdependent nature of any given experience.

If we are working to cultivate these awareness skills while dealing with regular pain, there’s a lot of benefit in referring to specialised sources, including a new book by Jon Kabbat-Zinn, the godfather of the popular mindfulness movement in the English-speaking world. Describing his approach to mindful pain-management, he points out:

Your unique experience, including the particular difficulties you face and thus have available to work with, all become essential elements of the work of mindfulness itself rather than obstacles to being mindful or impediments to the relief from pain that an ongoing practice of mindfulness can lead to.

With this attitude, there is no way to fail at this engagement because we are not trying to force anything to be other than as it is. We are simply learning how to hold it in awareness differently. Out of this gesture alone, the experience off Ian—and our relationship to it—can change profoundly.

See the book here: Mindfulness Meditation for Pain Relief by Jon Kabbat-Zinn

The heart of this approach is the application of awareness itself to pain. Being aware of the experience with curiosity and openness, while trying to drop some of the inner resistance and embellishment, can already be of much benefit, even before we go into the associated qualities of kindness and wisdom.

There are three potential results that people report experiencing as a result of such awareness practice. From most common to most unusual, they are:

1) The pain stays more or less the same, but becomes more psychologically bearable

2) The pain diminishes

3) The intensity of the stimulation experience remains the same, but it actually becomes somewhat pleasant

That being said, simple awareness practice can be largely elaborated upon. If we are suffering from chronic pain, there is more to do than simply changing our habits of awareness. We can establish powerful support systems, find communities, and explore our inner resources by following an elaborate strategy. A thorough approach to this has been outlined by Toni Bernhard in her following book (available also as an audio version:)

How to Live Well with Chronic Pain and Illness by Toni Bernard

Transforming our attitude to sickness and adversity

Of course, physical pain and sickness is just one of the multiple types of dukkha we experience, along with mental anguish, heartbreaking situations, catastrophes, war, and so on. Tibetan Buddhist tradition preserves a unique lineage of attitude-training practices (known as lojong) for transforming problems into the path. The teachings on those were largely responsible for attracting me to active Buddhist practice in college, and there’s one book in particular that I recommend on the topic—at least if you’re open to the Buddhist ideas of karma, rebirth, awakening and so on:

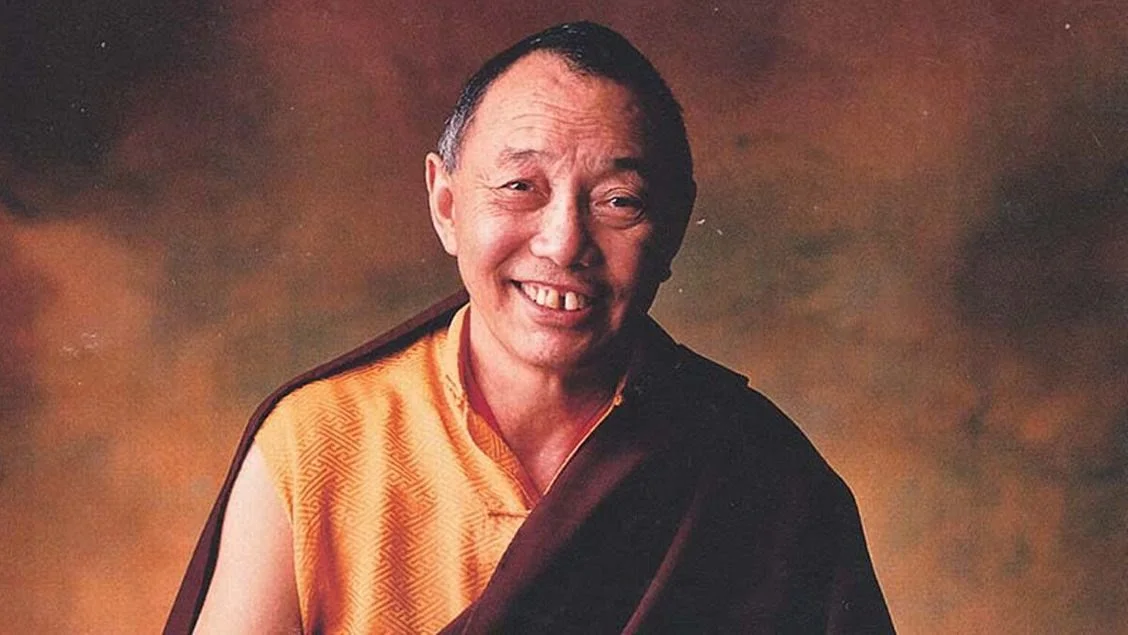

Transforming Problems into Happiness by Lama Zopa Rinpoche

The root text explained in this book was composed by the Third Dodrubchen Rinpoche, who also composed a very short and quintessential instruction on the theme of transforming sickness into the path, available here. While this set of suggestions requires additional instructions and extensive training, it provides extremely helpful pointers along the way to using pain as an aid on our path to awakening. There is also a similar text by Gyalse Togme Zangpo, the author of the “Thirty-seven practices of bodhisattvas”, translated here.

A fairly common practice for transforming pain into something meaningful—coming straight from the heart of the mind-training tradition—is tonglen (taking and giving) oriented towards our experiences of discomfort. Here’s a version of this practice led by me:

SoundCloud | InsightTimer | YouTube

Contemplative techniques to support the process of healing

Another theme to explore is the mental/spiritual side of healing. While not a substitute for qualified medical attention, some types of meditation can aid with an overall sense of wellbeing, or, potentially, increase the speed of our recovery (or at least ease the symptoms).

The Tibetan contemplative tradition has many practices of this nature and uses them to enhance the efficiency of Tibetan medicine. There are three wonderful sources on these healing meditations that I would recommend:

Ultimate Healing by Lama Zopa Rinpoche

The Healing Power of Mind by Tulku Thondup

Boundless Healing by Tulku Thondup

Some guided meditations from this category of practices (mostly centered around specific buddha-figures, or meditational deities) are available below:

White Tara Healing Practice: Inviting the Elements

Medicine Buddha: Rays of Healing Light

Guru Rinpoche Healing Practice

Orange Tara Dispelling Sickness

Finally, whatever type of pain or sickness we or our loved ones might be facing, a wonderful way to train is in the boundless bodhisattva aspirations—for example, the aspirations composed by Śāntideva. One particular verse recommended by Garchen Rinpoche for recitation (and, accordingly, deep contemplation) is as follows—may it be fulfilled for all of us:

May every being ailing with disease

Be freed at once from every malady.

May all the sickness that afflicts the living

Be instantly and permanently healed.